1. Introduction

Knowledge graphs have emerged as a compelling abstraction for

organizing world's structured knowledge over the internet, and a way

to integrate information extracted from multiple data

sources. Knowledge graphs have also started to play a central role in

machine learning as a method to incorporate world knowledge, as a

target knowledge representation for extracted knowledge, and for

explaining what is learned.

Our goal here is to explain the basic terminology, concepts and

usage of knowledge graphs in a simple to understand manner. We do not

intend to give here an exhaustive survey of the past and current work

on the topic of knowledge graphs.

We will begin by defining knowledge graphs, some applications that

have contributed to the recent surge in the popularity of knowledge

graphs, and then use of knowledge graphs in machine learning. We

will conclude this note by summarizing what is new and different

about the recent use of knowledge graphs.

2. Knowledge Graph Definition

A knowledge graph is a directed labeled graph in which the labels

have well-defined meanings. A directed labeled graph consists of

nodes, edges, and labels. Anything can act as a node, for example,

people, company, computer, etc. An edge connects a pair of nodes and

captures the relationship of interest between them, for example,

friendship relationship between two people, customer relationship

between a company and person, or a network connection between two

computers. The labels capture the meaning of the relationship, for

example, the friendship relationship between two people.

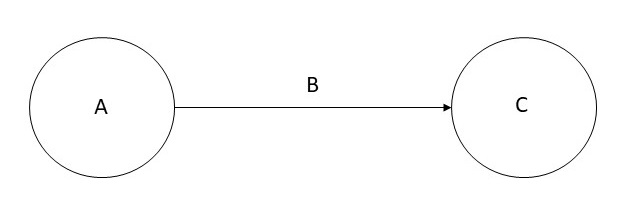

More formally, given a set of nodes N, and a set of

labels L, a knowledge graph is a subset of the cross

product N × L × N. Each member of this set is

referred to as a triple, and can be visualized as shown below.

The directed graph representation is used in a variety of ways

depending on the needs of an application. A directed graphs such as

the one in which the nodes are people, and the edges capture

friendship relationship is also known as a data graph. A directed

graph in which the nodes are classes of objects (e.g., Book,

Textbook, etc.), and the edges capture the subclass

relationship, is also known as a taxonomy. In some data

models, A is referred to as subject, B is

referred to as predicate, and C is referred to as

object.

Many interesting computations over graphs can be reduced to

navigating the graph. For example, in a friendship knowledge graph,

to calculate the friends of a friends of a person A, we can

navigate the knowledge graph from A to all nodes B

connected to it by a relation labeled as friend, and then

recursively to all nodes C connected by the friend relation to

each B.

A path in a graph G is a series of nodes

(v1, v2,..., vn) where for any i

∈ N with 1 ≤ i < n, there is an edge from vi to

vi+1. A simple path is a path with no

repeated nodes. A cycle is a path in which the first

and the last nodes are the same. Usually, we are interested in only

those paths in which the edge label is the same for every pair of

nodes. It is possible to define numerous additional properties over

the graphs (e.g., connected components, strongly connected

components), and provide different ways to traverse the graphs (e.g.,

shortest path, Hamiltonian path, etc.).

3. Recent Applications of Graphs

There are numerous applications of knowledge graphs both in research

and industry. Within computer science, there are many uses of a

directed graph representation, for example, data flow graphs, binary

decision diagrams, state charts, etc. For our discussion here, we

have chosen to focus on two concrete applications that have led to

recent surge in popularity of knowledge graphs: organizing information

over internet and data integration.

3.1 Graphs for organizing Knowledge over the Internet

We will explain the use of a knowledge graph over the web by taking

the concrete example of Wikidata. Wikidata acts as the central storage

for the structured data for Wikipedia. To show the interplay between

the two, and to motivate the use of Wikidata knowledge graph, consider

the city of Winterthur in Switzerland which has a page in

Wikipedia. The Wikipedia page for Winterthur lists its twin towns: two

are in Switerzland, one in Czech Republic, and one in

Austria. The city of Ontario in California that has a Wikipedia page

titled Ontario, California, lists Winterthur as its sister

city. The sister city and twin city relationships are identical as

well as reciprocal. Thus, if a city A is a sister city of another city

B, then B must be a sister city of A. This inference should be

automatic, but because this information is stated in English in

Wikipedia, it is not easy to detect this discrepancy. In contrast, in

the Wikidata representation of Winterthur, there is a relationship

called twinned administrative body that lists the city of

Ontario. As this relationship is symmetric, the Wikidata page for the

city of Ontario automatically includes Winterthur. Thus, when Wikidata

knowledge graph will be fully integrated into Wikipedia, such

discrepancies will naturally disappear.

Wikidata includes data from several independent providers, for

example, the Library of Congress that publishes data containing

information about Winterthur. By using the Wikidata identifier for

Winterthur, the information released by Library of Congress can be

easily linked with information available from other sources.

Wikidata makes it easy to establish such links by publishing the

definitions of relationships used in it in Schema.Org.

The vocabulary of relations in Schema.Org gives us, at

least, three advantages. First, it is possible to write queries that

span across multiple datasets that would not have been possible

otherwise. One example of such a query is: Display on a map the

birth cities of people who died in Winterthour? Second, with such a

query capability, it is possible to easily generate structured

information boxes within Wikipedia. Third, structured information

returned by queries also can appear in the search results which is

now a standard feature for the leading search engines.

A recent version of Wikidata had over 80 million objects, with over

one billion relationships among those objects. Wikidata makes

connections across over 4872 different catalogs in 414 different

languages published by independent data providers. As per the recent

estimate, 31% of the websites, and over 12 million data providers

publish Schema.Org annotations are currently using the vocabulary of

Schema.Org.

Let us observe several key features of the Wikidata knowledge

graph. First, it is a graph of unprecedented scale, and is the

largest knowledge graph available today. Second, it is being jointly

created by a community of contributors. Third, some of the data in

Wikidata may come from automatically extracted information, but it

must be easily understood and verified as per the Wikidata

editorial policies. Fourth, there is an explicit effort to provide

semantic definitions of different relation names through the

vocabulary in Schema.Org. Finally, the primary driving use

case for Wikidata is to improve the web search. Even though Wikidata

has several applications using it for analytical and visualization

tasks, but its use over the web continues to be the most compelling

and easily understood application.

3.2 Graphs for Data Integration in Enterprises

Data integration is the process of combining data from different

sources, and providing the user with a unified view of data. A large

fraction of data in the enterprises resides in the relational

databases. One approach to data integration relies on a global schema

that captures the interrelationships between the data items

represented across these databases. Creating a global schema is an

extremely difficult process because there are many tables

and attributes; the experts who created these databases are usually

not available; and because of lack of documentation, it is difficult

to understand the meaning of the data. Because of the challenges in

creating a global schema, it is convenient to sidestep this issue, and

convert the relational data into a database with the generic schema of

triples, ie, a knowledge graph. The mappings between the attributes

are created on as needed basis, for example, in response to addressing

specific business questions, and can themselves be represented within

a knowledge graph. We illustrate this process using a concrete

example.

Many financial institutions are interested in creating a company

knowledge graph that combines the internal customer data with the

data licensed from third parties. Some examples of such third party

datasets include Dunn & Bradstreet, S&P 500, etc. An example usage

of a company graph is to assess the risk while making loan

decisions. The external data contain information such as the

suppliers of a company. If a company is going through financial

difficulty, it increases the risk of awarding loan to the suppliers

of that company. To combine this external data with the internal

data, one has to relate the external schemas with the internal

company schema. Furthermore, the company names used in the external

sources have to be related to the corresponding customer identifiers

used by the financial institutions. While using a knowledge graph

approach to data integration, determining such relationships can be

delayed until they are actually required.

4. Graphs in Artificial Intelligence

Knowledge graphs, known as semantic networks, have been used as a

representation for Artificial Intelligence since the early days of

the field. Over the years, semantic networks were evolved into

different representations such as conceptual graphs and description

logics. To capture uncertain knowledge, probabilistic graphical

models were invented.

Orthogonal to the representation of knowledge, a central challenge

in AI is knowledge acquisition bottleneck, ie, how to capture

knowledge into the chosen representation in an economically scalable

manner. Early approaches relied on knowledge engineering. Efforts

to automate portions of knowledge engineering led to techniques such

as inductive learning, and the current generation of machine

learning.

Therefore, it is natural that the knowledge graphs are being used

as a representation of choice for storing the knowledge automatically

learned. There is also an increasing interest to leverage domain

knowledge that is expressed in knowledge graphs to improve machine

learning.

4.1 Graphs as the output of Machine Learning

We will consider how graphs are being used as a target output representation for

natural language processing and computer vision algorithms.

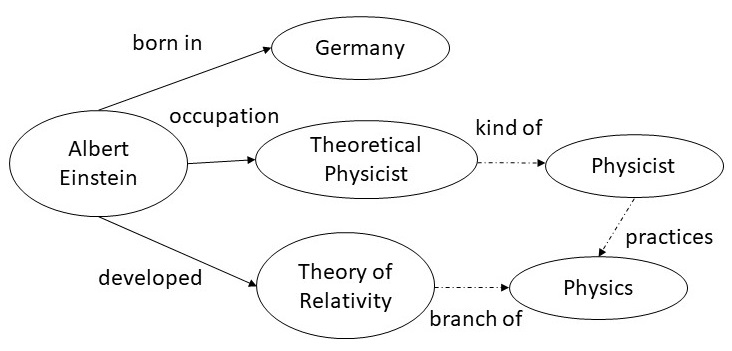

Entity extraction and relation extraction from text are two

fundamental tasks in natural language processing. The extracted

information from multiple portions of the text needs be correlated,

and graphs provide a natural medium to accomplish such a goal. For

example, from the sentence shown on the left, we can extract the

entities Albert Einstein, Germany, Theoretical Physicist, and

Theory of Relativity; and the relations born in, occupation and

developed. Once this snippet of the graph is incorporated

into a larger graph, we get additional links (shown by dotted edges)

such as a Theoretical Physicist is a kind of Physicist

who practices Physics, and that Theory of Relativity is

a branch of Physics.

| Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical

physicist who developed the theory of relativity.

|  |

|

|

A holy grail of computer vision is the complete understanding of an

image, that is, creating a model that can name and detect

objects, describe their attributes, and recognize their

relationships. Understanding scenes would enable important

applications such as image search, question answering, and robotic

interactions. Much progress has been made in recent years towards this

goal, including image classification and object detection.

For example, from the image shown above, an image understanding

system should produce a graph shown to the right. The nodes in the

graph are the outputs of an object detector. Current research in

computer vision focuses on developing techniques that can correctly

infer the relationships between the objects, such as,

man holding a bucket, and horse feeding from the bucket,

etc. The graph shown to the right is an example of a knowledge graph,

and conceptually, it like the data graphs that we introduced

earlier.

4.2 Graphs as input to Machine Learning

Popular deep machine learning models rely on a numerical input

which requires that any symbolic or discrete structures should first

be converted into a numerical representation. Embeddings that

transform a symbolic input into a vector of numbers have emerged as a

representation of choice for input to machine learning models. We

will explain this concept and its relationship to knowledge graphs

by taking the example of word embeddings and

graph embeddings.

Word embeddings were developed for calculating similarity

between words. To understand the word embeddings, we consider the

following set of sentences.

| I like knowledge graphs. | |

| I like databases. | |

| I enjoy running. | |

In the above set of sentences, we will count how often a word appears

next to another word, and record the counts in a matrix shown

below. For example, the word I appears next to the

word like twice, and next to word enjoy once, and

therefore, its counts for these two words are 2 and 1 respectively,

and 0 for every other word. We can calculate the counts for other

words in a similar manner to fill out the table.

| counts | I | like | enjoy | knowledge | graphs | databases | running | . |

| I | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| like | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| enjoy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| knowledge | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| graphs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| databases | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| running | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| . | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Above table constitutes a matrix which is often referred to

as word cooccurrence counts. We say that the meaning of each

word is captured by the vector in the row corresponding to that

word. To calculate similarity between words, we can simply calculate

the similarity between the vectors corresponding to them. In practice,

we are interested in text that may contain millions of words, and a

more compact representation is desired. As the above matrix is sparse,

we can use techniques from Linear Algebra (e.g., singular value

decomposition) to reduce its dimensions. The resulting vector

corresponding to a word is known as word embedding. Typical

word embeddings in use today rely on vectors of length 200. There are

numerous variations and extensions of the basic idea presented

here. Techniques exist for automatically learning word embeddings for

any given text.

Use of word embeddings has been found to improve the performance of

many natural language processing tasks including entity extraction,

relation extraction, parsing, passage retrieval, etc. One of the most

common applications of word embeddings is in auto completion of search

queries. Word embeddings give us a straightforward way to predict

the words that are likely to follow the partial query that a user has

already typed.

As a text is a sequence of words, and word embeddings calculate

co-occurrences of words in it, we can view the text as a graph in

which every word is a node, and there is a directed edge between

each word and another word that immediately follows it. Graph

embeddings generalize this notion for general network structure. The

goal and approach, however, remains the same: represent each node in

a graph by a vector, so that the similarity between the nodes can be

calculated as a difference between their corresponding vectors. The

vectors for each node are also referred to as graph embeddings.

To calculate graph embeddings, we define a method for encoding each

node in the graph into a vector, a function to calculate similarity

between the nodes, and then optimize the encoding function. One

possible encoding function is to use a random walk of the

graph and calculate co-occurrence counts of nodes on the graph

yielding a matrix similar to co-occurrence counts of words in

text. There are numerous variations of this basic method to

calculate graph embeddings.

We have chosen to explain graph embeddings by first explaining word

embeddings because as it is easy to understand them, and their use is

common place. Graph embeddings are a generalization of the word

embeddings. They are a way to input domain knowledge expressed in a

knowledge graph into a machine learning algorithm. Graph embeddings

do not induce a knowledge representation, but are a way to turn

symbolic representation into a numeric representation for consumption

by a machine learning algorithm.

Once we have calculated graph embeddings, they can be used for a

variety of applications. One obvious use for the graph embeddings

calculated from a friendship graph is to recommend new friends. A more

advanced tasks involve link prediction (ie, the likelihood of a link

between two nodes), etc. Link prediction in a company graph could be

used to identify potential new customers.

5. Summary

Graphs are a fundamental construct in discrete mathematics, and

have applications in all areas of computer science. Most notable uses

of graphs in knowledge representation and databases have taken the

form of data graphs, taxonomies and ontologies. Traditionally, such

applications have been driven by a top down design. As a knowledge

graph is a directed labeled graphs, we are able to leverage theory,

algorithms and implementations from more general graph-based systems

in computer science.

Recent surge in the use of knowledge graphs for organizing

information on the internet, data integration, and as an output target

for machine learning, is primarily driven in a bottom up manner. For

organizing information on the web, and in many data integration

applications, it is extremely difficult to come up with a top down

design of a schema. The machine learning applications are driven by

the availability of the data, and what can be usefully inferred from

it. Bottom up uses of knowledge graphs do not diminish the value of a

top down design of the schema or an ontology. Indeed, the Wikidata

project leverages ontologies for ensuring data quality, and most

enterprise data integration projects advocate defining the schema on

as needed basis. Machine learning applications also benefit

significantly with the use of rich ontology for making inferences from

the information that is learned even though a global ontology or a

schema is not required at the outset.

Word-embeddings and graph-embeddings both leverage a graph

structure in the input data, but they are necessarily more general

than knowledge graphs in that there is no implicit or

explicit need for a schema or an ontology. For example, graph

embeddings can be used over the network defined by exchange of

messages between nodes on the internet, and then used in machine

learning algorithms to predict rogue nodes. In contrast, for

the Wikidata graph, knowledge graphs in the enterprises, and

in the output representation of machine learning algorithms, a schema or ontology can play

a central role.

We conclude by observing that the recent surge in interest in

knowledge graphs is primarily driven by the bottom up requirements

of several compelling business applications. Knowledge graphs in

these applications can certainly benefit from the classical work on

the top down representation design techniques, and in fact, we

envision that eventually the two will converge.

|