1. Introduction

Once we have created the knowledge graph, we are interested in

retrieving information, and using that information to make new

conclusions. We have already introduced query languages using which we

can perform retrieval operations on the graph. In this chapter, we

will focus on inference algorithms, that go beyond retrievals, i.e.,

conclude new facts from the knowledge graph that are not explicitly

present in it. Inference algorithms can be invoked through the

declarative query interface.

We will consider two broad classes of inference algorithms: graph

algorithms, and ontology-based algorithms. The graph algorithms are

applicable to any graph-structured data, and support operations such

as finding minimum paths between nodes in a graph, identifying salient

nodes in a graph, etc. The ontology-based algorithms operate on the

structure of the graph but take its semantics into account, for

example, traversing specific paths, or concluding new connections

based on background domain knowledge. In this chapter, we will

consider both classes of these algorithms.

In principle, we could invoke graph algorithms, and the

ontology-based inference through a declarative query interface of

the sorts we have previously considered. Ontology-based inference

may leverage graph-based algorithms. For example, checking if an

object A is an instance of a class B, could be done by

checking whether a path exists in the class graph between C and B,

where C is the immediate type of A.

2. Graph-based Inference Algorithms

We will consider three broad classes of graph algorithms: path

finding, centrality detection, and community detection. Path finding

involves finding a path between two

or more nodes in a graph that satisfies certain properties. Centrality

detection is about understanding which nodes are important in a graph.

Different methods used to define the meaning of importance lead to

many variations in the centrality detection algorithms. Finally, community

detection is about identifying a group of nodes in a graph that

satisfies some criteria of being in a community. Community detection

is useful for studying emergent behaviors in graphs that may otherwise

not be noticed.

We will consider each of these categories of graph algorithms in

more detail. For each category, we will present an overview,

discuss different ways it is useful, and consider some sample

algorithms.

2.1 Path Finding Algorithms

There are several variations of the problem of finding paths in a

graph: finding the shortest path between any given two nodes, or

finding the shortest paths between all pairs of nodes, finding a

minimum spanning tree, etc. The shortest path between any given two

nodes can be used in planning an optimal route in a traffic navigation

system. A minimum spanning tree calculates the least cost for visiting

all the nodes in a set of nodes, and can be useful in problems such as

trip planning.

As an example of a specific shortest path algorithm, we will

consider the A* algorithm which is a generalization of the classical

Dijkastra's algorithm. A* algorithm is also widely used as a search

algorithm for solving AI Planning problems.

The A* algorithm operates by maintaining a tree of paths

originating at the start node and extending those paths one edge at a

time until its termination criterion is satisfied. At each step, it

determines which of the paths to extend based on the cost

of the path until now and the estimate of the cost required to extend

the path all the way to the goal. If n is the next node to

visit, g(n) the cost until now, and h(n) the estimate of

the cost required to extend the path all the way to the goal, then it

choose the node that minimizes f(n),

where f(n)=g(n)+h(n).

We must choose an admissible heuristic such that it never

over-estimates the cost of arriving at the goal. In one possible

variation, known as the best first search, the heuristic chooses the

path with the least overall cost until now, i.e., it

sets h(n)=0. There exists an extensive literature on the

different heuristics that can be used in the A* search.

2.2 Centrality Detection Algorithms

The centrality detection algorithms are used to better understand the

roles played by different nodes in the overall graph. This analysis can help

us understand the most important nodes in a graph, the dynamics of a

group and possible bridges between groups.

There are several variations of the centrality detection algorithm:

degree centrality, closeness centrality, between-ness centrality, and

page rank. Degree centrality simply measures the number of incoming

and/or outgoing edges. A node with a very high outgoing degree in a

supply chain network suggests a supplier monopoly. A closeness

centrality identifies nodes that have shortest paths to all other

nodes. Such information can be useful in identifying the location of a

new service so that it is most accessible to the widest range of

customers. Between-ness centrality identifies a node based on the number of

shortest paths between nodes that pass through it. Between-ness

centrality is a measure of the sphere of influence exercised by the

nodes in the network. Finally, the PageRank algorithm measures the

importance of a node based on other nodes it is recursively connected

to.

For our discussion here, we will consider the PageRank algorithm in

more detail. The Page rank was originally developed for ranking

pages for WWW search. It is able to measure the transitive

influence on a node. For example, a node connected to a few very

important nodes could be more important than the node connected to a

large number of unimportant nodes. We can define the PageRank of a

node as follows.

PR(u) = (1-d) + d * (PR(T1)/C(T1) + ... + PR(Tn)/C(Tn))

In the above formula, we assume that the node u has

incoming edges from nodes T1,...,Tn. We use d as a

damping factor which is usually set at 0.85. C(T1),...,C(Tn) is

the number of outgoing edges of nodes T1,...,Tn. The algorithm

operates iteratively by first setting the PageRank for all the nodes to

the same value, and then iteratively improving it for a fixed number of

iterations, or until the values converge.

Beyond its original use in ranking search results for WWW queries,

the PageRank has found many other interesting uses. For example, it

is used on social media sites to recommend who should a particular

user follow. It has also been used in fraud analysis to identify

highly unusual activity associated with nodes in a graph.

2.3 Community Detection Algorithms

The general principle underlying the community detection algorithms is

that the nodes in a community have more relationships within the

community than to nodes outside the community. Sometimes, the

community analysis can be the first step in analyzing a graph so that

a more in-depth analysis could be undertaken for nodes within the

community.

There are several flavors of community detection algorithms:

connected components, strongly connected components, label propagation

and fast unfolding. The first two of these algorithms, connected

components, and strongly connected components are frequently used in

the initial analysis of a graph. Connected components algorithm and strongly

connected components algorithm are standard techniques of graph theory. A

connected component is a set of nodes such that there is a path

between any two nodes in the underlying undirected graph. A strongly

connected component is a set of nodes such that for any given nodes A

and B in the set, there is a directed path from node A to node B, and path

from node B to node A. Both label propagation and fast unfolding are bottom

up algorithms for identifying communities in large graphs. We consider

both of these algorithms in more detail.

Label propagation begins by assigning each node in the graph to a

different community. We then arrange the nodes in a random order to

update their community as follows. We examine the nodes in the assigned order,

and for each node, we examine its neighbors, and set its community to

the community shared by a majority of its neighbors. The ties are

broken in a unform random manner. The algorithm terminates when each

node is assigned to a community that is shared by a majority of its

neighbors.

In the fast unfolding algorithm, there are two phases. We

initialize each node to be in a separate community. In the first

phase, we examine each node and each of its neighbors and evaluate

if there would be any overall gain in modularity in placing this

node in the same community as a neighbor. A suitable measure to

calculate modularity is defined. If there will be no gain, the node

is left in its original community. In the second phase of the

algorithm, we create a new network in which there is a node

corresponding to each community from Phase 1, and an edge between

the two nodes if there was an edge between some nodes in their

corresponding phase 1 communities. Links between the nodes of the

same community in phase 1 lead to self-loops for the node

corresponding to their community in Phase 2. Once Phase 2 is

completed, the algorithm repeats by applying phase 1 to the

resulting graph.

Both label propagation and fast unfolding algorithms reveal

emergent and potentially unanticipated communities. Different

executions may also lead to identification of different

communities.

3. Ontology-based Inference Algorithms

Ontology-based inference distinguishes a knowledge graph system

from a general graph-based system. We will categorize the

ontology-based inference into two categories: taxonomic inference and

rule-based inference. Taxonomic inference primarily relies on the

hierarchy of classes and instances and inheritance of values across

the hierarchy. Rule-based inference can involve general logical

rules. We can access ontological inference through a declarative

query interface, and thus, it can be used as a specialized

reasoning service for a certain class of queries.

3.1 Taxonomic Reasoning

Taxonomic reasoning is applicable in situations where it is useful to

organize knowledge into classes. Classes are nothing but unary

relations. We will consider the concepts of class membership, class

specialization, disjoint classes, value restriction, inheritance and

various inferences that can be drawn using them.

Both property graph and RDF data models support classes. For

property graphs, the node types are equivalent to classes. For RDF,

there is an extension called RDF schema that supports the definition

of classes. In more advanced extensions of RDF such as Web Ontology

Language and Semantic Web Rule Language, a full-fledged support is

available for defining classes and rules.

To discuss taxonomic reasoning, we have chosen to abstract away

from property graph and RDF data models. We will introduce the basic

concepts of taxonomies such as class membership, disjointness,

constraints and inheritance using Datalog as a specification language.

3.1.1 Class Membership

Suppose we wish to model data about kinship. We can define the

unary relations of male and female as classes, that

have members art, bob, bea, coe,

etc. The member of a class is referred to as an instance of that

class. For example, art is an instance of the

class male.

For every unary predicate that we also wish to refer to as a class, we

introduce an object constant with the same name as the name of the

relation constant as follows.

Thus, male is both a relation constant, and an object

constant. This is an example use of metaknowledge, and is

also sometimes known as punning.

To represent that art is an instance of the

class male, we introduce a relation

called instance_of and use it as shown below.

| instance_of(art,male) | instance_of(bea,female) |

| instance_of(bob,male) | instance_of(coe,female) |

| instance_of(cal,male) | instance_of(cory,female) |

| instance_of(cam,male) |

3.1.2 Class Specialization

Classes can be organized into a hierarchy. For example, we can introduce a class person. Both

male and female are then subclasses

of person.

| subclass_of(male,person) | subclass_of(female,person) |

The subclass_of relationship is transitive, ie, if A is a subclass of B, and

B is a subclass of C, then A is a subclass

of C. For example, if mother is a subclass

of female, then mother is also a subclass

of person

|

subclass_of(A,C) :- subclass_of(A,B) & subclass_of(B,C)

|

The subclass_of and instance_of relationships

are related in that if A is a subclass of B, then

all instances of A are also the instances of B. In

our example, all instances of male are also all the instances

of person

|

subclass_of(I,B) :- subclass_of(A,B) & instance_of(I,A)

|

A class hierarchy must not contain cycles, because that would imply

that a class is a subclass of itself, which is semantically incorrect.

3.1.3 Class Disjointness

We say that a class A is disjoint from another

class B if no instance of one can be an instance of another.

We can declare two classes to be disjoint from each other or a set of

classes to be a partition such that each class in the set is pairwise

disjoint from every other class. In our kinship example, the

classes male and female are disjoint from each

other.

| ~instance_of(I,B) :- disjoint(A,B) & instance_of(I,A) |

| ~instance_of(I,A) :- disjoint(A,B) & instance_of(I,B) |

| disjoint(A1,A2) :- partition(A1,...,An) |

| disjoint(A2,A3) :- partition(A1,...,An) |

| disjoint(An-1,An) :- partition(A1,...,An) |

3.1.4 Class Definition

Classes are defined using necessary and sufficient relation values. For example,

age is a necessary relation value for a person. If

we were to define the class of a brown-haired person, it is necessary

and sufficient for a person to have brown hair to be an instance of

this class.

| instance_of(X,brown_haired_person) :-

instance_of(X,person) & has_hair_color(X,brown)

|

The classes that have only necessary relation values are known

as primitive classes and the classes for which we know both

necessary and sufficient relation values are known as defined

classes. The sufficient definition of a class

has instance_of literal in its head.

3.1.5 Value Restriction

We can restrict the arguments of a relation to be instances of

specific classes. In the kinship example, we can restrict

the parent relationship so that its arguments are always

instances of the class person. Thus, if the reasoner is ever

asked to prove parent(table,chair), it can conclude that it

is not true simply by noticing that neither table

nor chair is an instance of person. The restriction

on the first argument of a relation is usually referred as

a domain restriction and the restriction on the second

argument of a relation is referred to as a range restriction. Similar

restrictions can be defined for higher arity relationships.

|

illegal :- domain(parent,person) & parent(X,Y) & ~instance_of(X,person)

|

|

illegal :- range(parent,person) & parent(X,Y) & ~instance_of(Y,person)

|

3.1.6 Cardinality and Number Consraints

We can further restrict the values of relations by specifying

cardinality and number constraints. A cardinality constraint

restricts the number of values of a relation, and the numeric

constraint specifies the range of numeric values that a relation may

take. For example, we may state that a person has exactly two

parents, and that the age of a person is between 0 and 100 years.

>

>

|

illegal :- instance_of(X,person) & ~countofall(P,parent(P,X),2)

| |

illegal :- instance_of(X,person) & age(X,Y) & min(0,Y,Y)

| |

illegal :- instance_of(X,person) & age(X,Y)& min(100,Y,100)

|

3.1.6 Inheritance

The relation values of a class are said to inherit to its

instances. For example, if we assert that art is an instance

of brown_haired_person, we can conclude

that has_hair_color(art,brown). In general, an object can be

an instance of multiple classes. In case of multiple inheritance, the

values inherited from different superclasses can conflict and cause

constraint violation. For example, if art is an instance of

the class brown_haired_person, and a

class bald_person with a constraint that the person has no

hair, we will have constraint violation. In case of constraint

violation, either the value causing the violation must be rejected, or

techniques for para-consistent reasoning must be used to manage such

inconsistency.

3.1.7 Reasoning with Classes

There are four broad classes of inference that are interesting with classes.

- Given two classes A and B, whether A

is a subclass of B?

- Given a class A and an instance I, whether I

is an instance of I?

- Given a ground relation atom determine whether it is true or false.

- Given a relation atom, determine different values of variables for which it is true.

The first two inferences are equivalent to computing the views

on subclass_of and instance_of relations. They

can also be implemented as path finding algorithms on the graph

defined by the classes and their instances. The last two inferences

are equivalent to the view on the relation atom of interest.

3.2 Rule-based Reasoning

It is not possible to draw a strict line between rule-based reasoning and

taxonomic reasoning. Even though we used Datalog as a specification language

for taxonomic reasoning, but it is possible to implement many of the desired

inferences in a rule engine. In this section, we will consider

an example of rule-based reasoning that leverages an advanced form of rules known

as existential rules. We will begin with an example knowledge graph that requires

such reasoning, and then we will consider rule-based reasoning algorithms to perform

the required reasoning.

3.2.1 Example Scenario Requiring Rule-based Reasoning

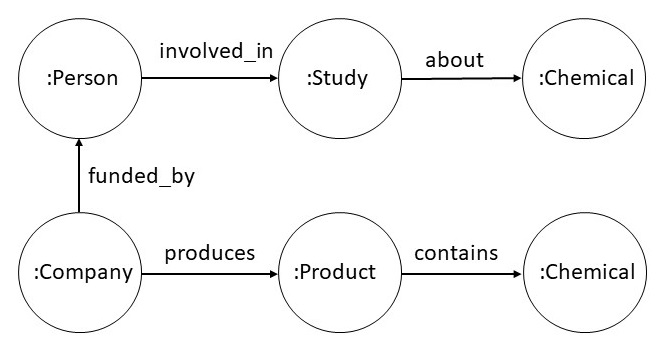

Consider a property graph with the schema shown below. Companies

produce products that contain chemicals. People are involved in studies

about chemicals, and they can be funded by companies.

Given the above property graph, we are interested in determining if a person

might have a conflict of interest in being involved in a study. We can define the

conflict relationship using the following Datalog rule.

|

coi(X,Y,Z) :-

involved_in(X,Y) & about(Y,P) & funded_by(X,Z) & has_interest(Y,P)

|

|

has_interest(X,Z) :- produces(X,Y) & contains(Y,Z)

|

The relation has_interest was not in the property graph

schema introduced above. But, with the help of its definition using a

rule, a rule engine can calculate the conflict of interest

relation coi. In some cases, we may be interested in adding the

computed values of the coi relationship to our knowledge

graph. As coi is a ternary relation, we will need to reify it.

As reification requires adding new objects in the graph, we can

specify it using an existential rule as shown below.

|

∃c conflict_of(c,X) & conflict_reason(c,Y) & conflict_with(c,Z) :-

involved_in(X,Y) & about(Y,P) & funded_by(X,Z) & has_interest(Y,P)

|

In general, existential rules are needed whenever we need to create new objects

in our knowledge graph. Relationship reification is an obvious such situation.

Sometimes, we may need to create new objects to satisfy certain constraints.

For example, consider the constraint: every person must have two parents. For a given

person, the parents may not be known, and if we want our knowledge graph to

remain consistent with this constraint, we must introduce two new objects representing

the parents of a person. As this can lead to infinite number of new objects, it is

typical to set a limit on how the new objects are created.

3.2.2 Approach for Rule-based Reasoning

To support rule-based reasoning on a knowledge graph, one usually interfaces a rule engine

with the data in the knowledge graph. We consider here a few different reasoning strategies

used by the rule engines.

In a bottom up reasoning strategy, also known as Chase, we apply

all the rules against the knowledge graph, and add new facts to it

until we can no longer derive new facts. As noted in the previous

section, we need to put in place aggressive termination strategies

to deal with situations where additional reasoning offers no

additional insight. Once we have computed the Chase, the reasoning

can proceed using traditional query processing methods.

In top down query processing, we begin from the query to be

answered, and apply the rules on as needed basis. A top down

strategy requires a tighter interaction between the query engine of

the knowledge graph with the rule evaluation. This approach,

however, can use lot less space as compared to the bottom up

reasoning strategy.

Highly efficient and scalable rule engines use query optimization

and rewriting techniques. They also rely on caching strategies to

achieve efficient execution.

4. Summary

In this chapter, we considered different inference algorithms for

knowledge graphs. Graph algorithms such as path finding, community

detection, etc. are supported by most practical graph engines. Graph

engines often provide limited support for ontology and rule-based

reasoning. Knowledge graph engines are now starting to become

available that support both general-purpsose graph algorithms as well

as ontology and rule-based reasoning.

|