1. Introduction

Once a knowledge graph has been constructed, we can ask questions

about it and use its contents to draw new conclusions. For example, a

query might retrieve the fact that Alice works for Intuit and that

and is located in California. Retrieval alone returns these

stored facts exactly as they appear in the graph. Inference goes a

step further: using these facts and the rules of inference, the

system can conclude that Alice recently moved to California, even if this

statement is not explicitly stored. In this chapter, we study

inference algorithms that enable such reasoning. These algorithms are

accessed through the same declarative query interface used for

retrieval, allowing users to seamlessly obtain both explicitly stored

facts and newly inferred ones.

We will consider two broad classes of inference algorithms: graph

algorithms and ontology-based algorithms. Graph algorithms use graph

operations such as finding shortest paths between nodes and

identifying important or influential nodes in a graph. Ontology-based

algorithms, in contrast, operate over the same graph structure but

explicitly take its semantics into account. For example, they may

traverse only semantically meaningful paths or infer new relationships

using background domain knowledge. In this chapter, we examine both

classes of algorithms and how they complement each other.

2. Graph-based Inference Algorithms

We will consider three broad classes of graph algorithms: path

finding, centrality detection, and community detection. Path finding

focuses on identifying paths between two or more nodes that satisfy

specific properties, such as minimal length or cost. Centrality

detection aims to determine which nodes are most important within a

graph. Because "importance" can be defined in different ways, a

variety of centrality measures and algorithms have been

developed. Finally, community detection seeks to identify groups of

nodes that are more strongly related to each other than to the rest of

the graph. Community detection is particularly useful for studying

emergent patterns and behaviors in graphs that may not be apparent

from local or pairwise relationships alone.

We will take a closer look at each of these categories of graph

algorithms. For every category, we will start with an overview, show

how it can be applied to real-world problems, and introduce a few

representative algorithms that illustrate the key ideas in action.

2.1 Path Finding Algorithms

Path-finding in a graph can take several forms. One common task is

finding the shortest path between two nodes -- the route that minimizes

the total cost of traveling along the edges. If the edges have no

weights, we simply count the number of steps. For example, in a city

map, the shortest path between two intersections might correspond to

the route that takes the fewest turns or covers the least

distance.

Another variation is computing a minimum spanning tree, which

connects all nodes in the graph using the least total cost. Imagine

planning a trip where you want to visit several landmarks while

traveling as little as possible; the minimum spanning tree helps

identify the most efficient set of connections.

Finally, we can also look at finding shortest paths between all

pairs of nodes, which can be useful for applications like routing

delivery trucks across a city or designing efficient communication

networks. These path-finding algorithms help us navigate and organize

complex networks in ways that are both practical and efficient.

As an example of a specific shortest-path algorithm, we will

consider the A* algorithm, which generalizes the classical Dijkstra's

algorithm. The A* algorithm not only finds the shortest path in a

graph but also uses a heuristic to guide the search, making it more

efficient in many cases. It is widely used in applications such as

route planning in maps and solving search problems in AI planning.

The A* algorithm operates by maintaining a tree of paths

starting from the initial node and extending those paths one edge at a

time until its termination criterion is satisfied. At each step, it

determines which of the paths to extend based on the cost of the path

until now and the estimate of the cost required to extend the path all

the way to the goal. If n is the next node to

visit, g(n) the cost until now, and h(n) the heuristic

estimate of the cost required to extend the path all the way to the

goal, then it chooses the node that minimizes

f(n)=g(n)+h(n).

This combination of actual cost and estimated remaining cost allows

A* to efficiently find a shortest path while prioritizing paths that

appear most promising.

To ensure that A* finds an optimal mapth, we must use

an admissible heuristic, meaning it never over-estimates the

true cost of arriving at the goal. One possible variation, known as

the best first search, ignores the remaining cost by

setting h(n)=0, effectively, choosing the path with the least

accumulated cost so far. There is an extensive literature on the

different heuristics that can be used in the A* search, each

offering trade-offs between efficiency and accuracy depending on the

problem domain.

2.2 Centrality Detection Algorithms

The centrality detection algorithms are used to better understand the

roles played by different nodes in the overall graph. This analysis can help

us understand the most important nodes in a graph, the dynamics of a

group and possible bridges between groups.

There are several common variations of centrality detection

algorithms: degree centrality, closeness centrality, betweenness

centrality, and PageRank.

- Degree centrality counts the number of incoming

and/or outgoing edges connected to a node. For example, in a supply

chain network, a node with a very high outgoing degree might

indicate a supplier with a monopoly.

- Closeness centrality identifies nodes that have

the shortest paths to all other nodes in the graph. This can help

determine optimal locations for new services so that they are

accessible to the widest range of customers.

- Betweenness centrality measures how often a

node lies on the shortest paths between other nodes, reflecting the

node's influence as a bridge or intermediary within the

network.

- PageRank assesses the importance of a node based on the importance of the nodes that link to it, using a recursive approach originally developed for ranking web pages.

Each of these measures highlights a different aspect of a node's

role and influence within a network.

For our discussion here, we will consider the PageRank algorithm in

more detail.

The PageRank algorithm was originally developed

for ranking web pages in search engines. It measures

the transitive influence of a node: a node connected to a few

highly important nodes may be considered more influential than a node

connected to many less important nodes. We can define the PageRank of

a node mathematically as follows.

PR(u) = (1-d) + d * (PR(T1)/C(T1) + ... + PR(Tn)/C(Tn))

In the above formula, the node u has incoming edges from

nodes T1,...,Tn. We use d as a

damping factor which is usually set at 0.85. C(T1),...,C(Tn)

is the number of outgoing edges of

nodes T1,...,Tn. The algorithm operates

iteratively by first setting the PageRank for all the nodes to the

same value, and then improving it for a fixed number of iterations,

or until the values converge.

Beyond its original use in ranking web pages for search

engines, PageRank has found many other interesting

applications. For example, it is used on social media platforms to

recommend which users a person might follow. It has also been applied

in fraud detection to identify nodes in a graph that exhibit highly

unusual or suspicious activity.

2.3 Community Detection Algorithms

The general principle underlying community detection

algorithms is that nodes within a community have more

connections to each other than to nodes outside the

community. Community analysis can often serve as a first step in

understanding a graph, allowing for more detailed analysis of nodes

and relationships within each identified community.

There are several variations of community detection

algorithms: connected

components, strongly connected

components, label propagation,

and Louvain

algorithm).

The first two, connected components and strongly connected components, are often used in the initial analysis of a graph. These are standard techniques from graph theory:

- A connected component is a set of nodes in an

undirected graph such that there is a path between any two nodes in

the set.

- A strongly connected component is a set of

nodes in a directed graph such that, for any two nodes A and B in

the set, there is a path from A to B and a path from B to A.

Both label propagation and fast unfolding are bottom-up algorithms

for identifying communities in large graphs. We will explore these two

algorithms in more detail in the following sections.

Label propagation begins by assigning each node in the graph to its

own community. The nodes are then processed in a random order. For

each node, we examine its neighbors and update the node's community to

match the community held by the majority of its neighbors. If there is

a tie, it is broken uniformly at random. The algorithm terminates when

every node belongs to a community that is shared by a majority of its

neighbors.

The fast unfolding algorithm operates in two phases. Initially,

each node is assigned to its own community.

In the first phase, the algorithm considers each node and its

neighbors and evaluates whether moving the node into a neighbor's

community would result in an overall increase in modularity, a measure

of the quality of a community partition. If no modularity gain is

achieved, the node remains in its original community.

In the second phase, a new, smaller network is constructed in which

each node represents a community identified in the first phase. An

edge is added between two nodes if there was at least one edge between

nodes in their corresponding communities in Phase 1. Edges between

nodes within the same community in Phase 1 become self-loops in the

new network.

After the second phase is completed, the algorithm repeats by

applying the first phase again to this newly constructed graph. This

process continues until no further improvement in modularity is

possible.

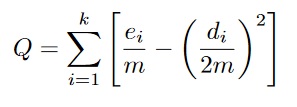

One example of a modularity function used in the above algorithm is

shown below.

In the above formula, we calculate the overall modularity

score Q of a network that has been divided into k

communities where ei and di are

respectively the number of nodes, and total degree of nodes in

community i, and m is the total number of edges in the

network.

Both label propagation and fast unfolding algorithms can reveal

emergent and potentially unanticipated communities in a graph. Because

these algorithms involve randomness or local optimization choices,

different executions may produce different community structures.

3. Ontology-based Inference Algorithms

Ontology-based inference is a key feature that distinguishes a

knowledge graph system from a general graph-based system. We

categorize ontology-based inference into two main types: taxonomic

inference and rule-based inference

Taxonomic inference relies on class hierarchies and instance

relationships, allowing properties and relationships to be inherited

across the hierarchy. Rule-based inference, in contrast, uses general

logical rules to derive new facts from existing ones. Ontological

inference can be accessed through a declarative query interface,

enabling it to function as a specialized reasoning service for certain

classes of queries.

We begin by introducing rule-based inference and then use it as a

foundation for explaining ontology-based inference more broadly.

3.1 Rule-based Inference

Many rule-based systems share a common foundation that can be

understood through a simple rule language called Datalog. In this

section, we introduce the basic form of Datalog, describe some useful

extensions, and explain how Datalog programs are evaluated. We

conclude with a real-world example that demonstrates how rule-based

inference can be applied in practice.

3.1.1 Datalog

A Datalog program consists of a finte set of facts and rules. Facts

are statements about the world, such as: "John is the father of

Harry". Rules describe how new facts can be derived from other facts,

for example, "If X is a parent of Y and if Y is a

parent of Z, then X is a grand-parent

of Z". Facts and rules are written as a clause of the following

form:

Each Li is a literal of the

form pi(t1,

... ,tn) such that pi is

a predicate symbol and the tj is

a term. A term is either a constant (representing a

specific object) or a variable (representing an unknown

object).

In a Datalog clause, The left-hand side is called its head,

and the right-hand side is called its body. The body of a

clause may be empty. Clauses with an empty body represent facts; while

clauses with at least one literal in the body represent rules.

For example, the fact that "John is the father of Harry" can be written

as father(john, harry). The rule "If X is a parent

of Y and if Y is a parent of Z, then X is

a grand-parent of Z" can be written as:

|

grand_parent(X,Z) :- parent(X,Y), parent(Y,Z)

|

In this example, the symbols parent

and grand_parent are predicate symbols, the

symbols john and harry are constants, and the

symbols X, Y and Z are variables.

Any Datalog program P must satisfy the

following safety conditions. First, each fact of P must

be ground, that is, it does not contain any variables. Second, every

variable that appears in the head of a rule of P must also

appear in the body of the that rule. These conditions guarantee that

the set of all facts that can be drived from a Datalog program is

finite.

A Datalog program determines what is true by starting from a set of

known facts and repeatedly applying rules until nothing new can be

inferred. The queries simply ask what can be derived from this

process.

3.1.2 Extensions to Datalog

In the basic form of Datalog introduced above, the negation sign

"~" is not allowed, and therefore, we cannot infer negative facts.

With a simple extension, also known as the closed world assumption,

we can infer negative facts: if a fact cannot be derived from a set

of Datalog clauses, then we conclude that the negation of this fact

is true. Negative facts are written as positive facts precded by the

negation symbol "~". For example, in the simple program introduced

until now, we can conclude ~parent(john, peter).

With the extension described above, we can also allow negated

literals in the bodies of rules. To guarantee a unique result, we need

to impose an additional condition called

stratification. Stratification requires that no predicate appearing in

the head of a rule can also appear negated in the body of the same

rule, either directly or indirectly through multiple rule

applications. This condition ensures that the Datalog program produces

a unique set of conclusions.>/p>

Pure Datalog is limited to reasoning over individual facts and does not

provide constructs for reasoning about collections of facts. In many

practical applications, however, it is necessary to compute aggregate

properties such as counts, minima, maxima, or sums. For this reason,

most practical Datalog engines support aggregate predicates

as an extension to the core language.

Aggregates allow a rule to refer to a set of values derived from the

body of the rule and to compute a single summary value over that set.

Common aggregates include count, sum, min,

max, and avg.

For example, the following rule computes the number of children for

each person:

|

num_children(X, N) :- countofall(Y, parent(X, Y), N).

|

Here, countofall binds N to the number of distinct

values of Y for which parent(X,Y) holds. The aggregate

is evaluated after all bindings for the body of the rule have been

determined.

Other important extensions to Datalog include the use of function

symbols, allowing disjunctions in the head of a rule, and supporting

negation that does not rely on the closed world assumption. These

features are generally supported in a family of languages known as

Answer Set Programming (ASP).

3.1.3 Evaluating Datalog Programs

o enable rule-based reasoning on a knowledge graph, a Datalog rule

engine is typically connected to the graph's data. In this section, we

will examine several reasoning strategies commonly used by Datalog

engines.

In a bottom up reasoning strategy, also known as the Chase, all

rules are against the knowledge graph, adding new facts until no

more facts can be derived. In some cases, it may be desirable to

put in place termination strategies to deal with

situations where additional reasoning offers no additional

insight. Once we have computed the Chase, the reasoning can proceed

using traditional query processing methods.

In top down query processing, we begin from the query to be

answered, and apply the rules on as needed basis. A top down

strategy requires a tighter interaction between the query engine of

the knowledge graph with the rule evaluation. This approach,

however, can use lot less space as compared to the bottom up

reasoning strategy.

Highly efficient and scalable rule engines use query optimization

and rewriting techniques. They also rely on caching strategies to

achieve efficient execution.

3.1.4 Example Scenario Requiring Rule-based Reasoning

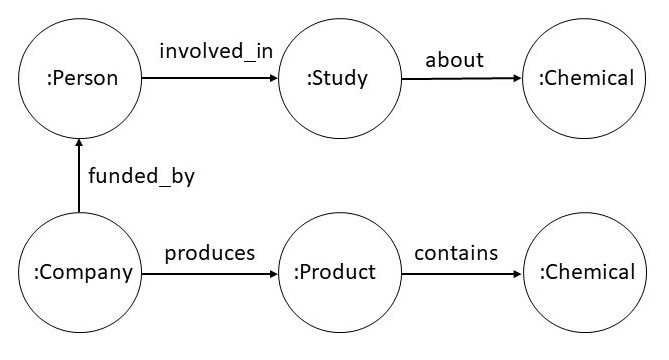

Consider a property graph with the schema shown below. Companies

produce products that contain chemicals. People are involved in studies

about chemicals, and they can be funded by companies.

Given this property graph, we may want to determine whether a person

could have a conflict of interest when participating in a study. We can define the

conflict relationship using the following Datalog rule.

|

coi(X,Y,Z) :-

involved_in(X,Y) & about(Y,P) & funded_by(X,Z) & has_interest(Y,P)

|

|

has_interest(X,Z) :- produces(X,Y) & contains(Y,Z)

|

The relation has_interest does not exist in the property graph

schema, but a rule engine can compute it using its definition.

Using this computed relation, the rule engine can derive

the coi relation.

In some cases, we may want to add the

computed values of the coi relation back into the knowledge

graph. As coi is a ternary relation, we need to reify it.

As reification requires adding new objects in the graph, we can

specify it using an existential rule as shown below.

|

∃c conflict_of(c,X) & conflict_reason(c,Y) & conflict_with(c,Z) :-

involved_in(X,Y) & about(Y,P) & funded_by(X,Z) & has_interest(Y,P)

|

In general, existential rules are needed whenever we need to

create new objects in a knowledge graph. Relationship reification

is a common example. Sometimes, we may need to create new

objects to satisfy certain constraints. For example, consider the

constraint: every person must have two parents. For a given person,

the parents may not be known, and if we want our knowledge graph to

remain consistent with this constraint, we must introduce two new

objects representing the parents of a person. As this can lead to

infinite number of new objects, it is typical to set a limit on how

the new objects are created.

3.2 Taxonomic Reasoning

Taxonomic reasoning is useful in situations where it is useful to

organize knowledge into classes. Classes can be thought of as unary

relations -- that is a set of objects that share a common property. In

this section, we will introduce the key concepts such as class

membership, class specialization, disjoint classes, value restriction,

inheritance and various inferences that can be drawn using them.

Both property graph and RDF data models support classes. In

property graphs, the node types correspond to classes. In RDF, an

extension called RDF schema (RDFS) allows the definition of

classes. More advanced RDF extensions such as the Web Ontology

Language (OWL) and the Semantic Web Rule Language (SWRL), provide

full support for defining classes and rules.

There is no strict boundary between rule-based reasoning and

taxonomic reasoning. We will use Datalog as a specification language

for taxonomic reasoning, and a Datalog engine can perform those inferences.

Specialized taxonomic reasoning systems, however, may leverage graph

algorithms that take advantage of the class hierarchies.

We will introduce the basic concepts of taxonomies such as class

membership, disjointness, constraints and inheritance using Datalog

as a specification language without making any specfic reference to

RDF or property graph model of graphs..

3.2.1 Class Membership

Suppose we wish to model data about kinship. We can define the

unary relations of male and female as classes, that

have members art, bob, bea, coe,

etc. The member of a class is referred to as an instance of that

class. For example, art is an instance of the

class male.

For every unary predicate that we also wish to refer to as a class, we

introduce an object constant with the same name as the name of the

relation constant as follows.

Thus, male is both a relation constant, and an object

constant. This is an example use of metaknowledge, and is

also sometimes known as punning.

To represent that art is an instance of the

class male, we introduce a relation

called instance_of and use it as shown below.

| instance_of(art,male) | instance_of(bea,female) |

| instance_of(bob,male) | instance_of(coe,female) |

| instance_of(cal,male) | instance_of(cory,female) |

| instance_of(cam,male) |

3.2.2 Class Specialization

Classes can be organized into a hierarchy. For example, we can introduce a class

person. Both male and female are then

subclasses of person.

| subclass_of(male, person) |

subclass_of(female, person) |

The subclass_of relationship is transitive. That is, if

A is a subclass of B, and B is a subclass of

C, then A is also a subclass of C. For example,

if mother is a subclass of female, then

mother is also a subclass of person.

|

subclass_of(A, C) :- subclass_of(A, B) & subclass_of(B, C)

|

The subclass_of and instance_of relationships are

closely related. If A is a subclass of B, then

every instance of A is also an instance of B.

In our example, all instances of male are also instances of

person.

|

instance_of(I, B) :- subclass_of(A, B) & instance_of(I, A)

|

A class hierarchy must not contain cycles. A cycle would imply that a

class is a subclass of itself, which is semantically incorrect and

undermines the meaning of specialization.

3.2.3 Class Disjointness

We say that a class A is disjoint from another class

B if no individual can be an instance of both classes at the

same time. We may explicitly declare two classes to be disjoint, or we

may declare a set of classes to form a partition, meaning that

the classes in the set are pairwise disjoint.

In our kinship example, the classes male and female

are disjoint. If an individual were inferred to be an instance of both,

this would indicate an inconsistency in the data. We capture such

inconsistencies using a distinguished atom illegal, which

signals that the condition specified in the body of the rule is not

allowed.

|

illegal :- disjoint(A, B) & instance_of(I, A) & instance_of(I, B)

|

|

disjoint(A1, A2) :- partition(A1, ..., An)

|

|

disjoint(A2, A3) :- partition(A1, ..., An)

|

|

disjoint(An-1, An) :- partition(A1, ..., An)

|

3.2.4 Class Definition

Classes can be defined using necessary and sufficient

relation values. A relation value is necessary for a class if

every instance of the class must satisfy it. For example,

age may be a necessary relation value for the class

person, since every person has an age, but having an age alone

is not sufficient to conclude that something is a person.

A relation value (or set of relation values) is sufficient for a

class if any individual that satisfies those relations can be inferred

to be an instance of the class.

For example, consider the class brown_haired_person. It is

both necessary and sufficient that an individual is a person

and has brown hair in order to belong to this class.

|

instance_of(X, brown_haired_person) :-

instance_of(X, person) &

has_hair_color(X, brown).

|

Classes that are described only using necessary relation values are

called primitive classes. In contrast, classes for which we

specify both necessary and sufficient relation values are called

defined classes.

In a rule-based setting, a sufficient class definition is characterized

by the presence of an instance_of literal in the head of the

rule, allowing the reasoner to infer class membership whenever the

conditions in the body are satisfied.

3.2.5 Value Restriction

Value restrictions constrain the arguments of a relation to be

instances of specific classes. In the kinship example, we may wish to

restrict the parent relationship so that both of its arguments

are always instances of the class person.

With such a restriction in place, if the reasoner is asked to prove

parent(table, chair), it can immediately conclude that this

fact is not true, since neither table nor chair is an

instance of person. Value restrictions thus act as integrity

constraints that rule out semantically invalid facts.

A restriction on the first argument of a relation is called a

domain restriction, while a restriction on the second argument

is called a range restriction. Similar restrictions can be

defined for relations of higher arity.

|

illegal :- domain(parent,person) & parent(X,Y) & ~instance_of(X,person)

|

|

illegal :- range(parent,person) & parent(X,Y) & ~instance_of(Y,person)

|

For example, if the knowledge graph contains the fact

parent(art, chair) and we know that art is a

person but chair is not, the range restriction will

cause the atom illegal to be derived, indicating an

inconsistency in the data or rules.

As with disjointness constraints, value restrictions do not derive new

facts but instead detect violations. Their correct interpretation

relies on the ability to infer negative facts (such as

~instance_of(chair, person)), typically under a closed world

assumption or a stratified form of negation.

3.2.6 Cardinality and Number Constraints

We can further restrict the values of relations by specifying

cardinality and numeric constraints. A cardinality

constraint restricts the number of values a relation may have for a

given argument, while a numeric constraint restricts the range of

numeric values that a relation may take.

For example, we may require that every person has exactly two parents,

and that the age of a person lies between 0 and 100 years.

|

illegal :- instance_of(X, person) &

~countofall(P, parent(P, X), 2).

|

|

illegal :- instance_of(X, person) &

age(X, Y) &

Y < 0.

|

|

illegal :- instance_of(X, person) &

age(X, Y) &

Y > 100.

|

The first rule expresses a cardinality constraint: for every instance

of person, the number of distinct values P such that

parent(P,X) holds must be exactly two. The aggregate predicate

countofall is assumed to return the number of distinct

bindings that satisfy its second argument.

The second and third rules express numeric constraints on the

age relation, ruling out values that fall outside the allowed

range. As with other constraints, these rules do not derive new facts

but instead detect violations by concluding illegal.

In practice, enforcing cardinality constraints may require additional

mechanisms beyond pure Datalog. If parent information is missing, a

reasoner may either report a violation, or -- when existential rules are

allowed -- introduce fresh objects to satisfy the constraint. To prevent

unbounded object creation, systems typically impose limits or adopt

restricted forms of existential reasoning.

3.2.7 Inheritance

When an object belongs to a class, it automatically takes on the

properties associated with that class. This process is known as

inheritance. For example, if we state that

art is an instance of the class

brown_haired_person, we can infer that

has_hair_color(art, brown) holds.

An object may belong to more than one class at the same time. While

this is often useful, it can lead to problems when different classes

impose conflicting requirements. For example, if

art is an instance of both

brown_haired_person and bald_person, one class

requires that art has hair, while the other requires that

art has no hair. These requirements cannot both be satisfied

and result in a contradiction.

When such conflicts occur, a reasoning system must decide how to handle

them. One approach is to reject the information that causes the

conflict. Another approach is to use specialized techniques, known as

paraconsistent reasoning, which allow reasoning to continue

even in the presence of inconsistent information.

3.2.8 Reasoning with Classes

When working with classes in a knowledge graph, there are four main types

of inference that are particularly useful:

-

Determining whether one class is a subclass of another. For example,

is male a subclass of person?

-

Determining whether a given object is an instance of a class. For

example, is art an instance of brown_haired_person?

-

Determining whether a specific fact (a ground relation atom) is

true or false. For example, is parent(art, cal) true?

-

Finding all possible values of variables that make a relation true.

For example, who are the children of art?

The first two types of reasoning -- subclass and instance checks -- can be

implemented as simple path-finding operations over the graph of classes

and instances. The last two types -- evaluating ground facts and computing

variable bindings -- are handled by a Datalog engine using its rule-based

inference mechanisms.

4. Summary

In this chapter, we explored different types of inference algorithms

for knowledge graphs. We discussed graph-based algorithms such as

path finding and community detection, which are widely supported by

practical graph engines. These engines typically provide only limited

support for ontology-based and rule-based reasoning. More recently,

knowledge graph engines have begun to emerge that support both

general-purpose graph algorithms and advanced reasoning capabilities,

enabling more sophisticated analysis and inference over complex

datasets.

5. Further Reading

An excellent reference for detailed description of different graph algorithms along with the code for Neo4j and Apache Spark graph databases is available in [Needham

& Hodler 2019]. A comprehensive account of Datalog and logic programming is available as a textbook [Genesereth

& Chaudhri 2020]. The description of the ontology based inference is inspired by a large scale knowledge construction project [Chaudhri

et. al. 2013]

[Needham

& Hodler 2019] Needham, Mark and Amy E. Hodler. Graph Algorithms:

Practical Examples in Apache Spark and Neo4j. OReilly Media,

2019. ISBN 9781492047681.

[Genesereth

& Chaudhri 2020] Genesereth, M., & Chaudhri,

V. K. (2020). Introduction to Logic Programming. Springer

International

Publishing. https://www.amazon.com/Introduction-Programming-Synthesis-Artificial-Intelligence/dp/3031004582/

[Chaudhri

et. al. 2013] Chaudhri, V. K., Heymans, S., Wessel, M., & Son,

T. C. (2013). Object-oriented knowledge bases in logic

programming. Theory and Practice of Logic Programming, 13(4-5), 1-12.

https://static.cambridge.org/content/id/urn:cambridge.org:id:article:S1471068413000112/resource/name/tlp2013022.pdf

Exercises

Exercise 6.1.

For the tiled puzzle problem shown below, we can define two different admissible heuristics: Hamming distance and Manhanttan distance. The Hamming distance is the total number of misplaced tiles. The Manhattan distance is the sum of the distance of each tile from its desired position. Answer the questions below assuming that in the goal state, the bottom right corner will be empty.

|

(a) |

What is the Manhattan distance for the configuration shown above? |

|

(b) |

What is the Hamming distance for the configuration shown above? |

|

(c) |

If your algorithm was using the Manhattan distance as a heuristic, what would be its next move? |

|

(d) |

If your algorithm was using the Hamming distance as a heuristic, what would be its next move? |

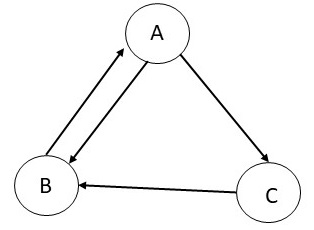

Exercise 6.2.

Consider a graph with three nodes and the edges as shown in the

table below for which we will go through first few steps of

calculating the Page rank. We assume that the damping factor is set

to 1.0. We initialize the process by setting the Page rank of each

node to 0.33. In the first iteration, as A has only one incoming

edge from B with a score of 0.33, and B has only one outgoing edge,

the score of A remains 0.33. B has two incoming edges --- the first

incoming edge from A (with a score of 0.33 which will be divided

into 0.17 for each of the outgoing edge from A), and the second

incoming edge from C (with a weight of 0.33 as C has only one

outgoing edge). Therefore, B now has a Page rank of 0.5. C has one

incoming edge from A (with a score of 0.33 which will be divided

into 0.17 for each of the outgoing edge from A), and therefore, the

Page rank of C is 0.17. Follow this process to calculate their ranks

at the end of iteration 2.

|

(a) |

What is the Page rank of A at the end of second iteration? |

|

(b) |

What is the Page rank of B at the end of second iteration? |

|

(c) |

What is the Page rank of C at the end of second iteration? |

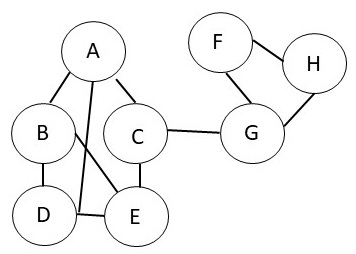

Exercise 6.3.

For the graph shown below, calculate the overall modularity score for

different choices of communities.

|

(a) |

What is the overall modularity score if all the nodes were in the same community? |

|

(b) |

What is the overall modularity score if we have two

communities as follows. The first community contains A, B and

D. The second community contains the rest of the nodes. |

|

(c) |

What is the overall modularity score if we have two

communities as follows. The first community contains A, B, C, D and

E. The second community contains the rest of the nodes. |

|

(d) |

What is the overall modularity score if we have two

communities as follows. The first community contains C, E, G and

H. The second community contains the rest of the nodes. |

Exercise 6.4.

Considering the statements below, state whether each

of the following sentence is true or false.

| subclass_of(B,A) | subclass_of(C,A) | subclass_of(D,B) |

| subclass_of(E,B) | subclass_of(F,C) | subclass_of(G,C) |

| subclass_of(H,C) | disjoint(B,C) | partition(F,G,H) |

|

(a) |

disjoint(D,E) |

|

(b) |

disjoint(B,G) |

|

(c) |

disjoint(F,G) |

|

(d) |

disjoint(E,C) |

|

(e) |

disjoint(A,F) |

Exercise 6.5.

Consider the following statements.

- George is a Marine.

- George is a chaplain.

- Marine is a beer drinker.

- A chaplain is not a beer drinker.

- A beer drinker is overweight.

- A Marine is not overweight.

|

(a) |

Which statement must you disallow to maintain consistency? |

|

(b) |

What are the alternative set of statements that might be true? |

|

(c) |

What conclusions you can always draw regardless of which statement you disallow? |

|

(d) |

What conclusion you can draw only some of the times? |

Exercise 6.6.

The goal of this exercise is to apply graph algorithms to the company

knowledge graph you created in Exercise 5.6. You will use path-finding,

centrality, and community-detection algorithms to analyze risks, causal

relationships, and business impacts represented in the graph.

You may use the suggested questions below as guidance. You are also

encouraged to formulate additional queries that reflect the structure

and semantics of your own knowledge graph.

Path-Finding Queries

Use shortest-path or constrained-path algorithms to analyze causal and

dependency relationships.

-

Identify the shortest or most relevant paths from external headwinds

(for example, macroeconomic risks or regulatory changes) to

revenue-related nodes. Which headwinds are closest, in graph

distance, to revenue impact?

-

How directly does a given macro risk affect the company? Measure

directness using path length, edge weights, or path constraints.

-

What is the shortest causal path explaining margin compression?

Interpret the result as a minimal causal narrative.

Centrality Analysis

Use centrality measures such as degree, betweenness, or PageRank to

identify influential nodes in the graph.

-

Which risks appear most structurally important in the graph?

Justify your answer using one or more centrality measures.

-

Which risks connect or propagate across multiple sectors or business

units? Identify nodes that play a bridging role.

-

Which factors are closest to, or most influential on, earnings-related

nodes?

Community Detection

Use community-detection algorithms to identify higher-level structure in

the graph.

-

Identify communities that represent coherent causal themes for the

company (for example, macroeconomic risk, competitive pressure, or

supply-chain disruption).

-

Which causal narratives are fragile? Identify communities that rely

on weak or sparse assumptions, such as low internal connectivity or

heavy dependence on a small number of edges.

-

Optional (advanced): If your graph includes data from multiple

earnings calls or time periods, identify which causal narratives

persist across time.

For each query, describe the algorithm used, the nodes or subgraphs

returned, and a brief interpretation of the result in business terms.

Visualizations are encouraged where appropriate.

Exercise 6.7. The goal of this exercise is to experiment with

ontology-based inference using the textbook knowledge graph you

created as part of Exercise 5.7. You will use class hierarchies,

constraints, and inherited properties to answer conceptual queries

about the graph.

Below are some suggested queries. You are encouraged to formulate

additional queries that are specific to the structure and semantics of

your own knowledge graph.

-

Describe a concept X. Your description should include:

the taxonomic relationships of X (such as its superclasses

and subclasses), all relation values associated with X

through inheritance or definition, and any applicable constraints.

-

How is concept X related to concept Y? Traverse

all relevant paths between X and Y in the ontology

and present the relationships in a clear and easy-to-understand

manner.

-

Compare two concepts X and Y. Explain how the two

concepts are similar and how they differ in terms of their

taxonomic relationships, relation values, and applicable

constraints.

For each query, explain which ontology-based inferences were used and

how they contributed to the final result.

|