1. Introduction

In previous chapters, we discussed how to design a knowledge graph,

how to construct it using different methods, and how to perform

inference over it. In this chapter, we shift our focus to how users

interact with a knowledge graph. User interaction is closely connected

to schema design: a well-designed schema is intended to be

understandable not only by machines, but also by people. One of the

key advantages of knowledge graphs is that the same conceptual model

of a domain, captured in the schema, also serves as the foundation for

the graph's implementation.

For example, in a knowledge graph about academic publications, the

schema may include concepts such as Paper, Author, and Venue, along

with relationships like writes and publishedIn. Because these concepts

closely reflect how users naturally think about the domain, a user can

explore the knowledge graph by asking questions such as "Which papers

did this author write?" or "Where was this paper published?" without

needing to understand how the data is physically stored.

In this chapter, we examine common interaction techniques that

become possible once a knowledge graph schema has been populated with

instances.

2. Modes of Interaction with a Knowledge Graph

The primary purpose of a knowledge graph is to help answer users'

questions. Some of these questions are known in advance, for example,

standard queries that support reports or dashboards, while others may

emerge only after users begin exploring the data or when the system

itself reveals unexpected patterns.

User interaction with a knowledge graph can take different

forms. In some cases, interaction happens in real time, such as when a

user submits a query and immediately receives results. In other cases,

interaction occurs through batch processes, where the knowledge graph

is analyzed offline to generate reports, summaries, or analytics for

later use.

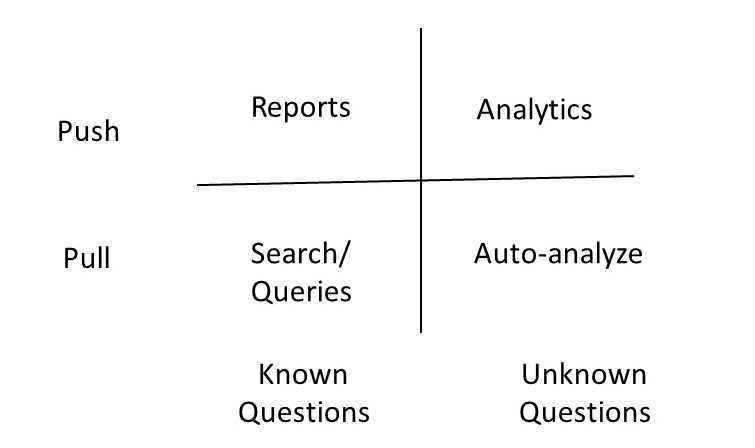

Together, these considerations lead to four broad modes of

interaction, which can be organized along two dimensions: whether the

interaction is initiated by the user (a pull model) or initiated by

the system in response to available information (a push model), and

whether the questions being answered are known in advance or emerge

dynamically. In the following sections, we examine each of these

interaction modes in more detail.

Figure 1: Different Modes for Interacting with a Knowledge Graph

Knowledge graph interaction modes are typically supported through a

combination of search, query answering, and graphical interfaces. For

example, in an academic publications knowledge graph, a user might

look for information about authors, papers, or venues. A search

interface resembles a search engine, allowing users to type keywords

such as an author's name or a paper title to quickly locate relevant

entities or facts. Query interfaces enable more precise questions, for

instance, a user could ask, "Which papers did Dr. Smith publish in

2024?", using either a formal query language or a natural language

interface. Graphical interfaces allow users to visualize

relationships, compose queries by connecting entities, and explore the

network of papers, authors, and venues interactively.

In practice, knowledge graph systems often combine these interface

types to support diverse user needs. For example, a query about an

author's publications might be composed using both keyword search

and a structured query builder, with the results displayed as a graph

showing authors linked to their papers, alongside a textual list of

publication details. In this section, we examine three key interface

types in detail -- graphical visualization, structured query

interfaces, and natural language queries -- focusing on how they help

users explore and retrieve knowledge effectively. Formal query

languages such as SPARQL and Cypher have been covered in previous

chapters, so our focus here will be on their practical application in

user -- facing interfaces.

3. Visualization of a Knowledge Graph

It is common to see graphical visualizations of knowledge graphs

containing thousands of nodes and edges. For example, a knowledge

graph showing all publications, authors, and citations in a large

research domain might render every paper and author at once, creating

a dense "hairball" that is difficult to interpret. These

visualizations often serve merely as a backdrop, rather than actively

contributing to insights or helping users identify the most important

patterns. Simply working with a knowledge graph does not automatically

make a graphical representation the best way to interact with

it. Instead, we should rely on established principles of visualization

design and select the medium that most effectively conveys the

intended information.

In this section, we begin by summarizing key visualization

principles, and then outline several best practices for visualizing

knowledge graphs in ways that support meaningful user interaction.

3.1 General Principles for Visualization Design

The purpose of visualizing a knowledge graph is to create a representation that significantly amplifies the user's understanding of the data. Effective visualizations help users by:

- Presenting more information than they could remember at one time.

- Highlighting important pieces of information, reducing the need to search.

- Placing relevant data next to each other to facilitate comparisons.

- Guiding attention as users navigate the visualization.

- Providing an abstract view by selectively omitting or recoding information.

- Allowing interaction, which supports deeper engagement and exploration of the data.

For example, in an academic publications knowledge graph, visualization can help a researcher quickly see patterns such as which authors collaborate most frequently, which papers are most cited, and how research topics are connected -- all without having to manually parse hundreds of records.

A visualization is an adjustable mapping from the data to a visual

form for a human perceiver. A Knowledge graphs is powerful because

its schema can be visualized directly in the same form in which it

is stored as a data, i.e., without requiring any transformation. We

should not assume this approach to always carry over when we are

visualizing the data stored in the knowledge graph, because, the

stored data size is much larger than the size of the schema. We, therefore,

need to explicitly undertake a design of visual structures for best

presenting knowledge graph data.

Designing a visual structure involves encoding information in several ways:

- Spatial substrate: Determining how elements are positioned. For instance, nodes representing authors might be arranged to minimize edge crossings, or papers could be grouped by topic.

- Marks: Visible elements such as points, lines, or areas that represent data values. In our example, nodes for papers might be circles, with the size representing citation count.

- Connections: Lines or edges that show relationships. Hierarchical or tree structures can be used for nested data, such as grouping papers under their respective authors.

- Enclosure: Shapes or borders that group related elements, like enclosing all papers from the same research lab.

- Retinal properties: Color, hue, saturation, transparency, or shape to highlight attributes. For example, papers could be colored by research area.

- Temporal encoding: Animation or time-based representation can show changes over time, such as the growth of citations for a particular paper or author network.

Visualizations can be grouped into four categories:

- Simple: Displays up to three variables, which is generally

considered the limit for easy human comprehension. For instance, a

scatter plot of papers by publication year, citation count, and

topic area.

- Composed: Combines multiple simple visualizations to show

additional variables, such as a scatter plot alongside a bar chart

of author collaborations.

- Interactive: Lets users explore and navigate the data. In our

academic knowledge graph example, a user could click on an author

node to expand connected papers or see co-authors.

- Attentive/Reactive: Responds to user actions and may anticipate

useful information. For example, when a researcher selects a highly

cited paper, the system could highlight related papers or emerging

topics automatically.

By following these principles, knowledge graph visualizations can

transform complex data into insights that are understandable,

actionable, and engaging for users.

3.2 Best Practices for Knowledge Graph Visualization

In the previous section, we reviewed principles for designing effective visualizations and emphasized that showing all data in a cluttered graph is rarely the best approach. In this section, we outline a step-by-step approach for designing knowledge graph visualizations that leverage these principles.

The design process can include the following steps:

- Determine which variables to encode in the spatial layout. For

example, in an academic publications knowledge graph, nodes

representing authors could be positioned to minimize edge crossings,

while papers could be grouped by research area.

- Combine multiple spatial encodings to increase dimensionality,

allowing different relationships or attributes to be represented

simultaneously.

- Use retinal properties, such as color, size, or shape, to add

additional dimensions of information. For instance, node size could

indicate citation count, and color could indicate research

area.

- Add interactive controls to allow selective exploration,

filtering, and zooming, so users can navigate the graph without

being overwhelmed.

- Incorporate attentive-reactive features, where the system

highlights relevant nodes or suggests related data elements based on

the user&s focus.

A practical visualization could include several key features. First,

an aggregated overview presents a summary of the data to help users

orient themselves. Users can then zoom into specific areas or pose

queries to focus on subsets of interest. While exploring a segment of

the knowledge graph, users can request details on individual nodes or

relationships. Finally, attentive-reactive features can proactively

suggest important papers, authors, or emerging topics, helping users

discover relevant information without needing to search exhaustively.

4. Structured Query Interfaces

A structured query interface (SQI) is an important way for users to interact with a knowledge graph. In such an interface, users start typing expressions, and the system suggests completions that can be mapped into an underlying query language, such as Cypher or SPARQL.

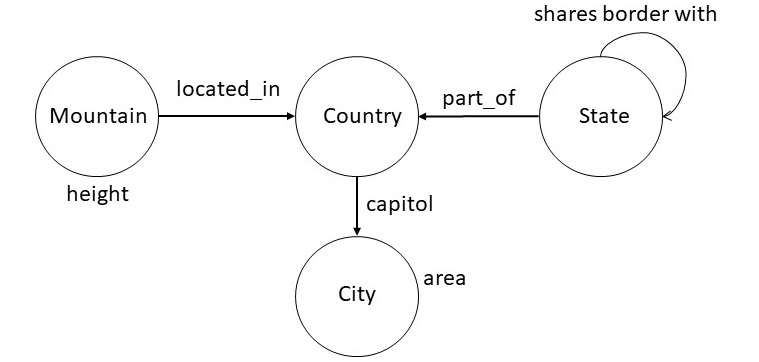

To illustrate, consider the following snippet of a knowledge graph schema from Wikidata:

Figure 2: A snippet of the Wikidata Schema

Based on this schema, users can pose queries such as:

- city with largest area

- top five cities by area

- countries whose capitals have area at least 500 square kilometers

- states bordering Oregon and Washington

- second tallest mountain in France

- country with the most number of rivers

One way to specify a structured query interface is to specify rules

of grammar in the Backus Naur Form (BNF). The rules shown below

illustrate this approach for the set of examples considered above.

| <np> ::= <noun> "and" <noun> |

| <np> ::= <geographical-region> | |

| <geographical-region> <spatial-relation> <geographical-region> |

| <geographical-region> ::= "capital of country" | "city" | "country" | |

|

"mountain" | "river" | "state" |

| <property> ::= "area" | "height" |

| <aggregate-relator> ::= "with the most number of" | "with largest" |"with" |

| <aggregate-modifier> ::= "top" <number> | "second tallest" |

| <spatial-relation> ::= "bordering" | "inside" |

| <number-constaint> ::= "atleast" <quantity> |

| <quantity> ::= <number> <unit> |

| <unit> ::= "Square Kilometer" |

| <ranking> ::= "by" |

We can reduce the queries above to expressions that conform to this

grammar. For example, the first query, "city with the largest

area", conforms to the following expression:

| <geographical-region> <aggregate-relator> <property> |

Next consider the query "top five cities by area". The following

expression that captures this query is equivalent to "top five city

by area". For our structured query interface to be faithful to

original English, we will need to incoporate the lexical knowledge

about plurals.

| <aggregate-modifier> <geographical-region> <ranking> <property> |

Finally, we show below the expression for the third query:

"countries whose capitals have area at least 500 squared

kilometers". The expression show below has the following version in

English: "country with capital with area at least 500 squared

kilometers". In addition to the incorrect pluralization, it uses

different words, for example, "with" instead of "whose", and "with"

instead of "have". Most reasonable speakers of English would consider

both the queries to be equivalent. This example highlights the

tradeoffs in designing structured query interfaces: they may not be

faithful to all the different ways of posing the query in English, but

they can handle a large number of practical useful cases. For

example, the above grammar will correctly handle the query "state with

largest area", and a numerous other variations.

| <geographical-region> <aggregate-relator> <geographical-region> |

| <aggregate-relator> <property> <number-constraint> <quantity> |

Once we have developed a BNF grammar for a structured query

interface that specifies the range of queries of interest, it is

straightforward to check whether an input query is legal, and also

to generate a set of legal queries which could be suggested to the

user proactively to autocomplete what they have already typed. We

show below a logic programming translation of the above BNF

grammar.

| np(X) :- np(Y) & np(Z) & append(X,Y,Z) |

| np(X) :- geographical_region(X) |

| np(A) :- geographical_region(X) & spatial_relation(Y) & geographical_region(Z) & append(A,X,Y,Z) |

| geographical_region(capital) |

| geographical_region(city) |

| geographical_region(country) |

| geographical_region(mountain) |

| geographical_region(river) |

| geographical_region(state) |

| property(area) |

| property(height) |

| aggregate_relator(with_the_most_number_of) |

| aggregate_relator(with_largest) |

| aggregate_relator(with) |

| aggregate_modifier(second_tallest) |

| aggregate_modifier(X) :- number(N) & append(X,top,N) |

| spatial_relation(bordering) |

| aggregate_relation(insider) |

| number_constraint(X) :- quantity(Q) & append(X,atleast,Q) |

| quantity(Q) :- number(N) & unit(U) & append(Q,N,U) |

| unit(square_kilomters) |

| ranking(by) |

Improvements in structured queries accepted by the system require

improving the grammar. This approach can be very cost-effective for

situations where the entities of interest and their desired

relationships can be easily captured in a grammar. In the next

section, we consider approaches that aim to accept queries in English,

and try to overcome the problem of required engineering of the grammar

through a machine learning approach.

5. Natural Language Query Interfaces

A possible approach to go beyond the structured queries, and to get

around the problem of massive engineering of the grammar, is to use a

semantic parsing framework. In this framework, we begin with a

minimal grammar and use it with a natural

language parser that is trained to

choose the most likely interpretation of a question. A semantic

parsing system for understanding natural language questions has five

components: executor, grammar, model, parser and learner. We briefly

describe each of these components and then illustrate them using

examples.

Unlike traditional natural language parsers that produce a parse

tree, a semantic parsing system produces a representation that can

be directly executed on a suitable platform. For example, it could

produce a SPARQL or a Cypher query. The engine that evaluates the

resulting query then becomes the executor for the semantic parsing

system.

The grammar in a semantic parsing system specifies a set of rules

for processing the input sentences. It connects utterances to

possible derivations of logical forms. Formally, a grammar is set of

rules of the form α ⇒ β. We show below a snippet

of a grammar used by a semantic parsing system.

| NP(x) with the largest RelNP(r) ⇒ argmax(1,1,x,r) |

| top NP(n) NP(X) by the RelNP(r) ⇒ argmax(1,n,x,r) |

| NP(x) has RelNP(r) at least NP(n) ⇒ (< arg(x,r) n) |

The first rule in the above grammar can be used to process "city

with the largest area". The right-hand side of each rule specifies an

executable form. For the first rule, argmax(m,n,x,r) is a

relation that consists of a ranked list of x (ranked

between m and n) such that the ranking is defined on

the r values of x. Similarly, the third rule handles the

query "countries whose capital has area at least 15000 square

kilomter". In the right hand side of the rule,

(< arg(x,r), n) specifies the computation to determine those x such that their

r value is less than n.

Given an input question, the application of grammar may result in

multiple alternative interpretations. A model defines a probability

distribution over those interpretations to specify which of them is

most likely. A common approach is to use the log-linear machine

learning model that takes as input the features of each

interpretation. We define the features of

an interpretation by maintaining a vector in which each position is

a count of how many times a particular rule of the grammar was

applied in arriving at that interpretation. The model also contains

another vector that specifies the weight of each feature for

capturing the importance of each feature. One goal of the learning

then is to determine an optimal weight vector.

Given a trained model, and an input, the parser computes its high

probability interpretation. Assuming that the utterance is given as a

sequence of tokens, the parser (usually a chart parser), recrusively

builds interpretations for each span of text. As the total number of

interpretations can be exponential, we typically limit the number of

interpretations at each step to a pre-specified number (e.g., 20). As a

result, the final interpretation is not guaranteed to be optimal, but it

very often turns out to be an effective heuristic.

The learner computes the parameters of the model, and in some

cases, additions to the grammar, by processing the training

examples. The learner optimizes the parameters to maximize the

likelihood of observing the examples in the training data. Even

though we may have the training data, but we do not typically have

the correct interpretation for each instance in the data. Therefore, the

training process will consider any interpretation that can reproduce an

instance in the training data to be correct. We typically use a

stochastic gradient descent to optimize the model.

The components of a semantic parsing system are relatively loosely

coupled. The executor is concerned purely with what we want to express

independent of how it would be expressed in natural language. The

grammar describes how candidate logical forms are constructed from the

utterance but does not provide algorithmic guidance nor specifies a way

to score the candidates. The model focuses on a interpretation

and defines features that could be helpful for predicting

accurately. The parser and the learner provide algorithms largely

independent of semantic representations. This modularity allows us to

improve each component in isolation.

Understanding natural language queries accurately is an extremely difficult

problem. Most semantic parsing systems report an accuracy in the

range of 50-60%. Improving the performance further requires

amassing training data or engineering the grammar. Overall success

of the system depends on the tight scope of the desired set of

queries and availability of training data and computation power.

6. Summary

In this chapter, we explored the various ways end-users can interact

with knowledge graphs. The key takeaway is that simply displaying many

nodes and edges on a screen is rarely the most effective

approach. Graphical views can be useful for understanding the schema,

which is typically small and structured, but they are often less

effective for exploring instance-level data.

Designing an effective interface requires considering the business

problem, the type of data, and the resources available for interface

development. In practice, the best interfaces often combine multiple

interaction methods: search for quickly locating information,

structured queries for precise data retrieval, and natural language

question answering for limited, targeted use cases. For example, a

user might start with a search to find a city, refine results with a

structured query, and then ask a natural language question to compare

specific properties across cities.

By thoughtfully combining these approaches, we can design knowledge

graph interfaces that are both usable and informative, supporting

real-world decision-making rather than just visual exploration.

7. Further Reading

The discussion on visualization design in this chapter draws on the

work of Stu Card, which provides many detailed examples and

illustrations of effective visualization

principles [Card

2008]. For readers interested in structured queries, these can be

seen as a subset of controlled natural languages, which have also been

used for knowledge capture. Our examples in this chapter focus on

controlled language solely for querying purposes. A good starting

point for a more extensive discussion is Kowalski's position

paper

[Kowalski 2020].

Natural language query interfaces have been explored extensively

through semantic parsing. Percy Liang's work demonstrates how a

semantic parser can map user questions into formal queries over a

knowledge

graph [Liang

2016]. This approach allows precise translation of natural

language into SPARQL or Cypher queries while handling variations in

phrasing.

Much recent research leverages large language models (LLMs) to

generate queries over knowledge graphs. For example, given a question

like "Which countries have capitals with an area greater than 500

km2?", an LLM can be prompted with the schema and example queries to

produce the equivalent SPARQL query. Accuracy improves significantly

when the model has access to schema

information [Allemang

& Sequeda 2024]. Due to the unpredictable performance of

current LLMs, a common strategy is to have the model map input

questions to a set of predefined query templates in SPARQL or Cypher,

combining natural language understanding with precise, tested query

structures.

Graphistry is a

commercial company focused on the visual aspects of leveraging

knowledge graphs. Their work illustrates how high-quality

visualizations can help users explore complex relationships, uncover

insights, and make sense of large-scale knowledge graph data,

highlighting the value of visualization in a comprehensive knowledge

graph offering.

[Card

2008] Card, S. K. (2008). Information visualization. In

J. A. Jacko & A. Sears (Eds.), The Human Computer Interaction

Handbook: Fundamentals, Evolving Technologies and Emerging

Applications (pp. 509-543). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

[Kowalski

2020] Kowalski, R. (2020). Logical English. Position paper

prepared for Logic and Practice of Programming (LPOP) 2020.

[Liang

2016] Liang, P. (2016). Learning executable semantic parsers for

natural language understanding. Communications of the ACM, 59(9),

68-76. https://doi.org/10.1145/2866568

[Allemang & Sequeda

2024] Allemang, D. & Sequeda, J. F. (2024). Increasing the LLM

Accuracy for Question Answering: Ontologies to the Rescue! arXiv

preprint arXiv:2405.11706. https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.11706

Exercises

Exercise 7.1.

How does visualization amplify the user understanding of a knowledge graph?

|

(a) |

By presenting impressive graphs |

|

(b) |

By using beautiful colors |

|

(c) |

By presenting a more abstract view of a situation by omission and recoding of information |

|

(d) |

By using optimal graph layout algorithms |

|

(e) |

By leveraging machine learning to better understand a user |

Exercise 7.2.

Which of the following is not a step in the process of designing a visual structure?

|

(a) |

Choice of retinal properties |

|

(b) |

Identifying and presenting time varying information |

|

(c) |

Fine tune the features for machine learning |

|

(d) |

Choosing a spatial substrate |

|

(e) |

Choosing suitable axes and coordinates |

Exercise 7.3.

What is an attentive reactive visualization?

|

(a) |

It is a simple visualization in which we show upto three different pieces of information. |

|

(b) |

It is a visualization in which we combine one or more simple visualizations with the goal of capturing more variables in the same display. |

|

(c) |

It is a visualization in which the response of the interface depends on how a user interacts with it. |

|

(d) |

It is a visualization in which the user can selectively explore, expand and navigate information. |

|

(e) |

It is a visualization that uses heptic devices. |

Exercise 7.4.

Which of the following queries does not follow from the BNF grammar considered in Section 3?

|

(a) |

capitol of country with second tallest mountain |

|

(b) |

mountain bordering river |

|

(c) |

city inside mountain with the most number of river |

|

(d) |

top 100 cities by Square Kilometer |

|

(e) |

country with the most number of state |

Exercise 7.5.

Which of the following statements is false?

|

(a) |

Given an input English sentence, it often leads to multiple alternative interpretations. |

|

(b) |

Semantic parser can be trained to choose the interpretation that has the highest probability of being correct. |

|

(c) |

The machine learner of a semantic QA system is capable of learning arbitrary extensions to the grammar. |

|

(d) |

A semantic parsing system requires a manually engineered grammar. |

|

(e) |

We still require a large number of training examples to get a good performance on a semantic parsing system. |

Exercise 7.6. In this exercise, your goal is to design a

user interface for the company knowledge graph you have been building

in the previous chapters. Choose one of the use case scenarios below

and apply the principles and techniques discussed in this chapter,

including visualization, structured queries, and natural language

interfaces. Your interface should leverage the queries and inferences

you have developed so far, and you should be able to demonstrate how a

user can explore the knowledge graph effectively.

- Company Insight: Create a 360-degree view of a

company that combines information from multiple sources. Using data

from Wikidata, SEC filings, or other public sources, design an

interface that presents an integrated view of the company. The

interface should allow users to search, query, and visualize the

information. Consider adding filters, dashboards, or summaries to

help users quickly grasp key insights.

Example task: Allow a user to find the top five companies with the highest revenue in the last fiscal year, and visualize how their subsidiaries are connected across different regions.

- Causal Graph: Explore headwinds and tailwinds

that might affect a company's performance. Design an interface

that visualizes causal relationships, incorporating inferences such

as shortest paths, communities, and centrality measures derived from

your knowledge graph. Users should be able to navigate, query, and

visualize these relationships to understand potential drivers of

company performance.

Example task: Allow a user to identify which market events are most likely to influence a company's stock performance and display the causal pathways connecting these events to financial outcomes.

Optional extensions: Include a short justification for

your design choices, highlighting how your interface supports user

interaction with the knowledge graph. You may provide sketches,

screenshots, or a prototype built using tools such as Dash, Streamlit,

or Neo4j Browser.

Exercise 7.7. Design a user interface to integrate the textbook knowledge graph into an actual online textbook. Please refer to this online video as an example of an existing interface. This interface combines elements of search, visualization, and structured queries. Consider the following scenarios when designing your new interface:

- First-Time Learning: Assume the student is

approaching the textbook for the first time. They may not fully

understand all concepts and might have gaps in prior knowledge.

Example task: Allow the student to explore the knowledge graph to see prerequisite concepts, get definitions, and visualize relationships among new topics, helping them navigate the material more effectively.

- Exam Revision: Assume a student is preparing

for an exam. The interface should help them review key concepts,

test their knowledge, and build confidence.

Example task: Provide a tool that lets the student answer practice questions generated from the knowledge graph, highlight relevant sections in the textbook, and visualize connections between concepts.

Optional extensions: Include a short rationale for your design decisions, showing how your interface supports effective learning. You may provide mockups, annotated screenshots, or a working prototype using tools such as Jupyter Book, Streamlit, or web frameworks.

|